The Old Woman Under the Tree

It is three days after my arrival in India and I am in Bhopal, in the Central Indian state of Madhya Pradesh. Despite being the site of the worst chemical accident in history, it seems quite an ordinary city, a provincial capital, ancient but unhistorical. I am staying with friends and they’ve loaned me their car and driver so I can go see the sights.

Early in the morning, before it’s begun to get hot, Mateen and I head out of the city. Already the streets are choked with traffic of a kind I’ve never before experienced: the traffic of diesel buses competing with cars, competing with rickshaws, competing with scooters, competing with bicycles, competing with people, and all deferring to cows.

We stall in this traffic for a long time, inching through the streets of old Bhopal. My friends live in the new city of genteel middle-class apartment buildings, wide empty roads, and patches of flowers munched by country goats. But here, by the mosque and the old city wall, the chaos is complete. As I breathe in its scent along with that of the diesel, I see a young woman wandering through the street. Her hair is shorn, her clothes dirty, her feet bare. She weaves in and out of traffic, her face a blank slate of tragedy. I find myself staring at her, unable to look away. I say to myself, “Please, let’s move, let’s move. Let’s move before she gets close, let’s move before I can see into her eyes.” Just in time we lurch onwards, and my gaze is taken away. We cross the railroad tracks, and in fits and starts make it out into the country. But her image stays with me, even as the city melts into hills and forests.

Mateen speaks very little English, but he tries hard to be a good guide. He’s enjoying the day out―a whole day to drive around and see things. Usually he spends his day taking my host from the apartment to work, and then picking him up for lunch, and then taking him back to work again. Now, he says to me, “Sanchi.” And we drive to Sanchi.

Once we’re out of the car, walking among the ancient stupas of the Emperor Ashoka’s golden Buddhist age, he points at things and calls them by name “Stupa.” “Stupa.” “Stupa.” “Old.” “Old.” “Old.” I try to lose him. I want to spend a moment on my own in the tranquility.

I shake off the traffic and the woman and the diesel, and sit looking down on the fields of Madhya Pradesh spread out below. They are verdant from the monsoon and covered with trees colored a shade of green I have never seen before. Are they a bit more yellow, a bit more blue? But too soon Mateen finds me, and makes me move on like a good tourist.

“Vidisha Caves.” The car whips along the road away from Sanchi, whips by those blue-green-yellow trees. We reach Vidisha, a small market town, and Mateen gets lost in its back streets. Again, urban life emerges and cuts to the core. No trees or flowers or ancient works of art soften the edges. Careening down the narrow alleys, people’s faces are thrust in front of me, inescapable. I stare into their eyes; they stare right back into mine. An open sewer runs alongside the road, alongside the doors to people’s houses. A toddler steps outside and defecates into the gutter. I feel the peace of Sanchi slip out of my head.

Eventually Mateen finds the road to the caves, a country road lined with tall, thin trees. It winds over a river where women are pounding saris against the rocks, and naked little boys are squealing while having a swim. At the end of the road, the Udaigiri caves appear, lonely landmarks, baking in the sun like so many tandoori ovens. A local man relieves Mateen of his guide duties. He proudly shows us the boar’s head incarnation of Vishnu, the beautiful carving that puts Vidisha on the map. Then Mateen waits by the car while the guide leads me to the other carvings in the harder-to-get-to caves. The drive over the river has brought back a little of the peace, but it is too, too hot for this sightseeing. I feel ill with the dust and the sun and the chaos that still bubbles underneath. But I clamber up the scorching rock and down into one cave and then up again and down into another. I will probably never see these caves again. It would be a shame if I missed something.

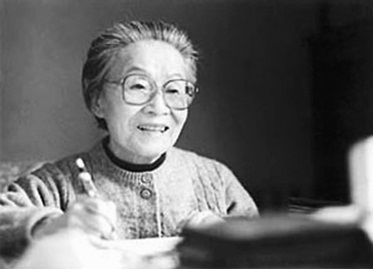

Finally, we are done. We descend the side of the rocky cliff and I head straightaway for the car. An ancient woman in a yellow sari sits nearby, shaded by a small tree. As I pass she greets me by saying, “Ram Ram”―invoking the name of God not once, but twice. I look into the woman’s eyes and in that moment see calm instead of chaos. It is a still moment of purity of place.

Desire for this type of moment is what brought me to India. But in the stillness I realize that I now have a new desire. It’s a newly found thirst not for this one perfect moment of purity, but for the orchestra of dissonance that has led up to it―the diesel madness of Bhopal, the strange green hills of Sanchi, the twisting back lanes of Vidisha, the hot, historic Udaigiri caves. This all is India and I am in the thick of it. You can’t have the peace without the chaos.

As the old woman keeps my gaze, I fold my hands in a namaste.

Then Mateen opens the car door, and calls for the tourist to move on.

Bhopal,” he says. “Home.”

树下的老婆婆

这是我来印度的第三天。作为印度中央邦的首府,博帕尔市曾经发生过印度历史上最严重的化学泄露事故,城市虽然古旧,却缺乏历史沉淀的风韵,在印度各大城市中毫不起眼。我寄宿在朋友家中,他们为我安排了汽车和司机方便我四处观光。

一大早,赶在天气变得炙热之前,我和马田往城外出发。街上早已是车水马龙,拥挤的交通状况是我前所未见的――柴油公共汽车、小车、黄包车、三轮车、自行车和行人争相抢道,但是无一例外的他们都给牛让路。

我们被困已经很久了,只能在旧城区的大街上慢慢前行。我朋友住在新城区,里面尽是中产阶级的高尚住宅楼,有宽敞空旷的大道,还有野山羊在嚼着路边的鲜花。但在这里,在清真寺和旧城墙下,却是最为彻底的喧嚣。空气中除了汽油的味道,还夹杂着其他各种不同的味道。我忽然看到一个姑娘在路边徘徊,她有一头短发,穿着褴褛,还赤着双脚。在车流中漫无目的地穿梭,她的神情是那么的呆滞悲哀。我一下子就被她吸引住了,眼睛一直盯着她看,根本无法移开。可我心底却在默念:“拜托,拜托,快点开,快点开,我不想靠近看到她的眼!”汽车很及时地在这个时候开动了,我终于得以挣脱出来。我们穿过铁轨,一路走走停停地出了城外,映入我们眼帘的是山坡和树林,但那姑娘的影子一直在我脑海里挥之不去。

马田只能说一点点英语,可看得出他很努力地想把今天的导游工作做好。因为通常他都是负责接送雇主上下班,中午接他出去吃饭,然后又把他送回办公室。今天他却可以驾车逛上一整天,因此他显得很放松愉快,冲我说了一句:“桑吉,”然后我们就往桑吉进发。

下车后,我们在佛塔中间穿行。这些佛塔都是在阿育王统治时期兴建的,从中可以看到往昔佛教的兴盛。马田一边指指点点,一边说着“佛塔。”“佛塔?”“佛塔。”“古老。”“古老?”“古老。”我试图摆脱他,希望可以一个人静静地呆一会。

我坐了下来,眺望着脚下连绵的大地,喧嚣的交通、挥之不去的姑娘,还有汽油味道统统都被抛在了脑后。大地在季风雨的滋润下郁郁葱葱,茂盛的树木组成大块大块的绿色。我看着这片以前从未见过的风景,想着这绿色是偏黄多一点还是偏深绿多一点,可惜很快马田就发现了我,我只好像一个听话的游客乖乖地上路。

“我们去维迪沙石窟!”汽车沿着公路驶离桑吉,我们在沿途看见了很多黄黄绿绿的树木,树木的枝杈还不时地打在窗玻璃上。我们来到了维迪沙小镇,小街小巷很快让马田迷失了方向。同样的,处处可见城市化的景象,还有愈演愈烈的趋势。乡村与城镇交界的地方没有任何过渡,没有树木,没有鲜花,也没有古老的艺术作品。侧身穿行在横街窄巷中,我必须直面路人的脸,无法回避。我直视他们的眼睛,他们也同样直视着我。路两旁是没有遮盖的下水道,连接千家万户。一个蹒跚学步的幼童走出来就直接往水沟里排便。我知道桑吉的宁静正悄悄地从我脑海中溜走。

终于马田找到了前往石窟的路,那是一条乡村公路,两旁各一排高高细细的树。沿路有一条河,洗衣服的女人在河边把纱丽往石头上拍,光着身子的小男孩在玩水嬉戏,不时大声尖叫。到了路的尽头,乌代格里石窟终于出现在眼前。它孤独地矗立在阳光下,像许许多多的唐杜里炉。一个当地人接替马田成为我的导游。他很自豪地引领我们参观吡湿奴神的猪头化身雕刻,正是这座美丽的雕刻使维迪沙名闻遐迩。然后马田回到车旁等候,导游则带我到其他人迹罕至的石窟,继续参观里面的雕刻。一路沿着河走让我重新平静下来一点,可惜天气实在太热,破坏了兴致。在尘埃和阳光里我感到不适,那种喧嚣仿佛挥之不去。但是我还是坚持了下来,在炙热的岩石和山洞之间攀上爬下,因为我知道可能以后都不会再来这里,如果现在不抓紧看而漏过什么的话,将来我一定会后悔的。

终于,参观完毕。从陡峭的石崖下来,我径直往汽车方向走去。只见旁边的树荫下坐着一位头戴黄纱丽的老婆婆,在我经过的时候,她念了两句神灵的名字:“Ram Ram”,她不是念一遍,而是两遍。我注视着她的眼睛,我看到的是完全的平静,没有任何喧嚣的痕迹,那一刻,时空都仿佛为之停止,只剩下一片静谧。

正是出于这种对静谧的渴求吸引我来到印度。但是在寂静中,我突然意识到另一种新的渴求。它不再是寂静本身,而是这种寂静的前奏――由博帕尔的喧嚣、桑吉的翠绿山峦、维迪沙的羊肠小道,和炙热古老的乌代格里石窟交织碰撞出来的不协调之音。这就是印度,我走入了她的心脏。没有经历过喧嚣,就无法找到平和。

专注地看着那位老婆婆,我双手合十致谢。

然后马田打开车门,告诉我要上路了。

“博帕尔,”他说。“家。”